Our Reality

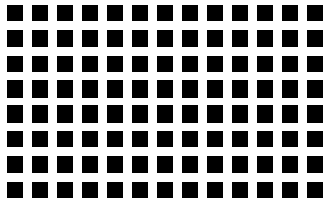

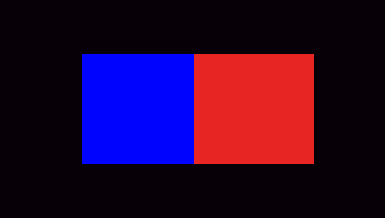

The red rectangle appears to be in front of the blue one. We can see grey dots in between the black squares. What you see is a mix of truth and imagination. Light goes in your eyes correctly, but that information is not accurately conveyed to the perception arena in your mind. Seeing is supposed to be believing. However, do you believe there are grey dots in the avenues between the black squares? Do you believe the red rectangle is closer to you than the blue one? If we can be fooled by illusions, how much faith can we put in our reality? We certainly live in our own personal reality. Everyone’s set of colour receptors are different. What you see is different to what others see.

Technology has helped those born with no vision and those that are unable to hear. This technological help doesn’t provide an instant transformation akin to turning on a television though. Patients aren’t suddenly granted a full colour picture with sublime sound. Implants provide the source, but the mind needs to learn to see and learn to decipher sounds. All of us did when we were young. We learned to hear and learned to see. It takes time to comprehend and make sense of the world.

Think about pictures and photographs. Do you instantly recognise what is being depicted every time? Most pictures will give us no trouble whatsoever, but some are such that we can’t determine what the picture is of. We have to look at it for a while or enlarge it in order to make sense of it. We may then re-see it entirely. A shape shifting transformation happens right before our eyes. We don’t have the capacity to take in every pixel of what is available. We can also see things that are not there, temporarily.

Fog can create a speed illusion. The fog alters our perception of speed making it feel as though we are driving slower than what we are. This can make people drive faster than they realise. We think the moon gets bigger when it is lower on the horizon. We make lots of judgement errors. We recall key points rather than memorise every word of a story. We understand the gist of something as opposed to memorising every piece of data. Some of the data is stored, some is omitted, some is condensed, some is garbage. We learn to live with errors that lead to us to mishear, mis-see things. We accept errors occur. However, we take offence when our rational thinking is called into question. Our imagination can create and fill in what we want to see. Our imagination can filter out what goes against our beliefs.

Life is not as it seems. We live by feelings. Things create an impression. We form emotive attachments rather than detailed characterisations. Whilst there is plenty of opportunity to get things wrong, some people are loath to admit they are wrong. Our sanity is called into question. Any mistake we make originated in the mind, did it not. Anything we get wrong relates to our mind, one way or another. That can be because we didn’t look closely enough or didn’t pay enough attention or stored a memory poorly.

We make spelling mistakes. We acknowledge them with little fuss. If we drop something, we just put it down to our fallibility, an accident. Spelling errors, breaking things unintentionally are caused by an error of sorts somewhere in the machine in our head. The commands come from there. Why then is it so hard for many of us to accept that our sight and imagination areas are likely to make mistakes too.

We call on many different areas of our mind to see. It is not just one area connected to our eyes. We have processing parts elsewhere that play a significant role in our visual system. There is a continuous flow of information back and forth between these different areas with experience resources aiding the process. That aiding helps us understand what is around us much quicker but is renowned for making do, putting what it thinks ought to be there. We therefore need to determine whether the information was seen, imagined, or contrived. Most of the time this all works well. Fatigue can set in, or random chaos can interrupt the normal process of laying down memories. The biggest error we can make of all, is the belief that we remember things correctly all the time.

Much of what you witness turns out to be imaginary. Our mind fills in countless blanks. It fills it in with what we would expect or are accustomed to seeing. Our belief that things are real is tested when our minds fuse reality with imagination. Part truth mixed with part fantasy – along with countless inconsistences.

Our perception of time can be manipulated. Time seems to slow down during a car crash for instance. We get the order of events muddled as we lay down memories in an incorrect sequence. Hocus pocus is generated by our mind’s frequent errors of perception. The unwillingness to consider likely explanations for occasional oddities that we experience leads to a whole host of crazy conjectures. We might believe that our sight system is as perfect as any camera, and we always interpret what enters our eyes accurately. If only that were the case. Eyewitness accounts have been shown to contradict videographic evidence.

People have stayed awake for days at a time. Dreams vividly overlay reality. If you want to experience what it is like to have a ghostly encounter, you can do the same. Stay awake for a long period of time. Hallucinations will begin. These bizarre sightings give you a deep understanding of how your imagination mingles with the information entering your eyes.

Regular habits lay down strong pathways in our mind. A blip in the routine can cause a mental re-enactment moments before doing it once again. The prediction of what you are about to do, so closely timed with the event has been given a name, déjà vu. It is nothing supernatural, the mind doesn’t behave in a reliable consistent fashion all the time.

Our friends are more than just a name. They have a set of habits. They have an image. We store lots of information about people. Lots of associations embedded including time points, smells, and events we went to. When one of these associations are brought to the fore you may think of your friend. Therefore, it should not be that astonishing if that friend pays you a visit or phones you soon after. A subconscious prediction is made. If you analyse it closely you may notice that that person has a particular habit albeit one that is not easily identifiable at first sight. Hence “I was just thinking about you and then you called me.” The mind is a machine that has a hazy, imprecise method of operation. It is in flux. It builds, repairs itself and degrades. It is a mush in the physical and metaphorical sense. We notice oddities. The missing brick in the wall, the different colour of one object, something that happens less frequently.

How do we know for sure we are awake? This edition fails to answer that simple question. We know in ourselves that we are not dreaming right now. Some might argue that we can pinch ourselves and feel the pain. I am certain that I have experienced pain whilst dreaming though. I have dreamt about dreaming. I know I am dreaming in part because it feels different somehow. Many events in the dream are not possible in the awake world. That provides a reasonable clue to the fact that I am dreaming. I have made sensible calculations, mathematical calculations that differed-not to the ones I make when fully awake. Dreaming and imagining are related. We assume that all that we see is played out in reality whereas what we see is rather contrived in our heads. Our existence is a mixture of sleepwalking, active participation in the world about us, and imagining, dreaming. The answer to the question of whether we are awake or not lies in the understanding that going to sleep is a mode of operation. We are still influenced by sounds, temperature, and movement. Our senses do not shut down, we simply ignore them more when asleep. Our attention is shifted from interaction using our body to focusing on interaction with our imagination.